History of the Regent's Canal

NOTE - THIS IS JUST RAW INFORMATION THAT IS ALREADY AVAILABLE TO THE PUBLIC. SOME OF THIS COULD BE RECYCLED IN OUR DISPLAYS.

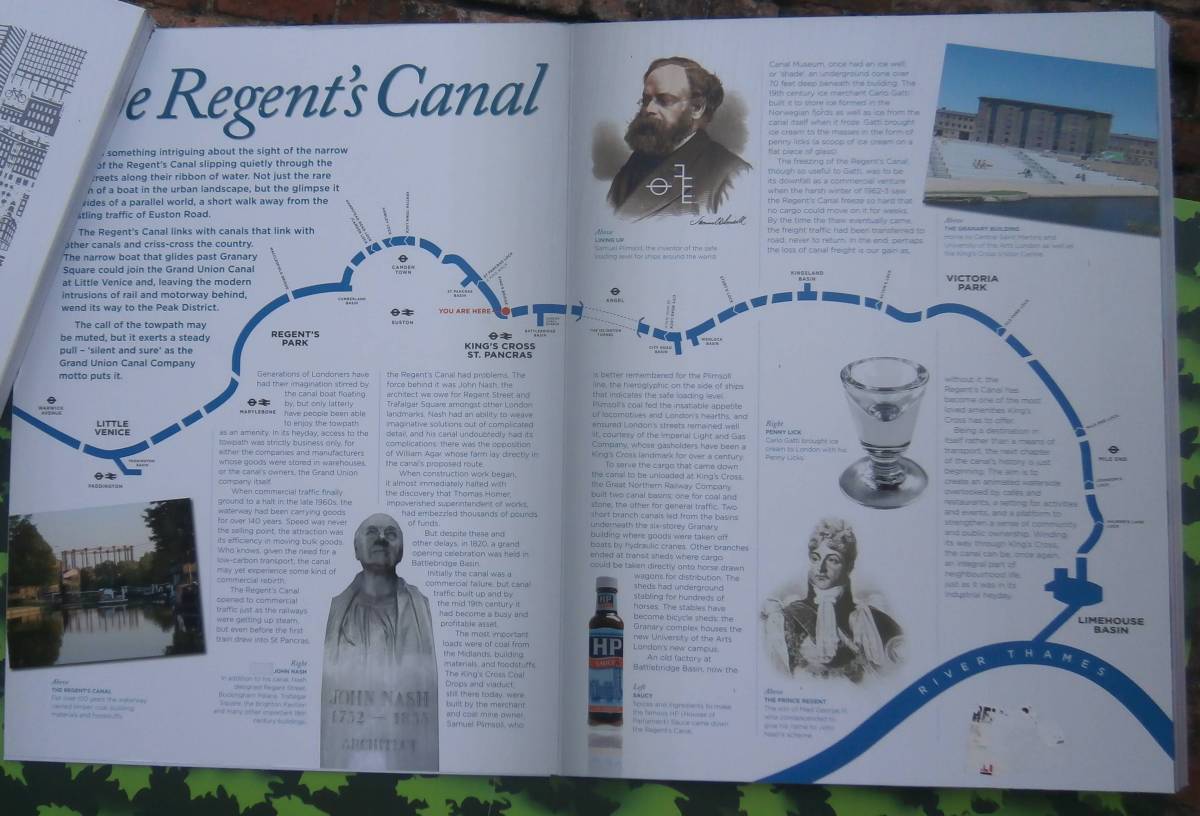

Information Boards at Granary Square |

|

Comment: The following text has been displayed at the bottom of the steps below Granary Square. It contains some interesting historical information about the life of canal, but towards the end it becomes apparent that this is promotional material for the re-development. It contains mixed messages about the desirability of freight traffic and it contradicts other historical information about the early success of the canal. However, the map is very useful. |

|

There is something intriguing about the sight of the narrow boats(?) of the Regent's Canal slipping quietly through the streets

along their ribbon of water. Not just the rare ??? of a boat in the urban landscape, but the glimpse it provides of a parallel world,

a short walk away from the bustling traffic of Euston Road.

The Regent's Canal links with canals that link with other canals and criss-cross the country. The narrow boat that glides past Granary Square could join the Grand Union Canal at Little Venice and, leaving the modern intrusions of rail and motorway behind, wend its way to the Peak District. The call of the towpath may be muted, but it exerts a steady pull - 'silent and sure' as the Grand Union Canal Company motto puts it. Generations of Londoners have had their imaginations stirred by the canal boat floating by, but only latterly have people been able to enjoy the towpath as an amenity. In its heyday, access to the towpath was stricly business only, for either the companies and manufacturers whose goods were stored in warehouses, or the canal's owners, the Grand Union company itself. When commercial traffic finally ground to a halt in the late 1960s, the waterway had been carrying goods for over 140 years. Speed was never the selling point, the attraction was its efficiency in moving bulk goods. Who knows, given the need for a low-carbon transport, the canal may yet experience some kind of commercial rebirth. The Regent's Canal opened to commercial traffic just as the railways were getting up steam, but even before the first train drew into St Pancras, the Regent's Canal had problems. The force behind it was John Nash, the architect we owe for Regent Street and Trafalgar Square amongst other London landmarks. Nash had an ability to weave imaginative solutions out of complicated detail, and his canal undoubtedly had its complications: there was the opposition of William Agar whose farm lay directly in the canal's proposed route. When construction work began, it almost immediately halted with the discovery that Thomas Homer, impoverished superintendent of works, had embezzled thousands of pounds of funds. But desipte these and other delays, in 1820, a grand opening celebration was held in Battlebridge Basin. Initially the canal was a commercial failure, but canal traffic built up and by the mid 19th century it had become a busy and profitable asset. The most important loads were of coal from the Midlands, building materials, and foodstuffs. The King's Cross Coal Drops and viaduct, still there today, were built by the merchant and coal mine owner, Samuel Plimsoll, who is better remembered for the Plimsoll line, the hieroglyphic on the side of ships that indicates the safe loading level. Plimsoll's coal fed the insatiable appetitie of locomotives and London's hearths, and ensured London's streets remained well lit, courtesy of the Imperial Light and Gas............. ......boats by hydaulic cranes. Other branches ended at transit shed where cargo could be taken directly onto horse drawn wagons for distribution. The sheds had underground stabling for hundreds of horses. The stables have become bicycle sheds: the Granary complex houses the new University of the Arts London's new campus. An old factory at Battlebridge Basin, now the Canal Museum, once had an ice well, or 'shade'; an underground cone over 70 feet deep beneath the building. The 19th century ice merchant Carlo Gatti built it to store ice formed in the Norwegian fjords as well as ice from the canal itself when it froze. Gatti brought ice cream to the masses in the form of penny licks (a scoop of ice cream on a flat piece of glass). The freezing of the Regent's Canal, though so useful to Gatti, was to be its downfall as a commercial venture when the harsh winter of 1962-3 saw the Regent's Canal freeze so hard that no cargo could move on it for weeks. By the time the thaw eventually came, the freight traffic had been transferred to road, never to return. In the end, perhaps the loss of canal freight is our gain as, without it, the Regent's Canal has become one of the most loved amenities King's Cross has to offer. Being a destination in itself rather than a means of transport, the next chapter of the canal's history is just beginning. The aim is to create an animated waterside overlooked by cafes and restaurants, a setting for activities and events, and a platform to strengthen a sense of community and public ownership. Winding its way through King's Cross, the canal can be, once again, an integral part of neighbourhood life, just as it was in its industrial heyday. |

Information Boards in each Borough

|

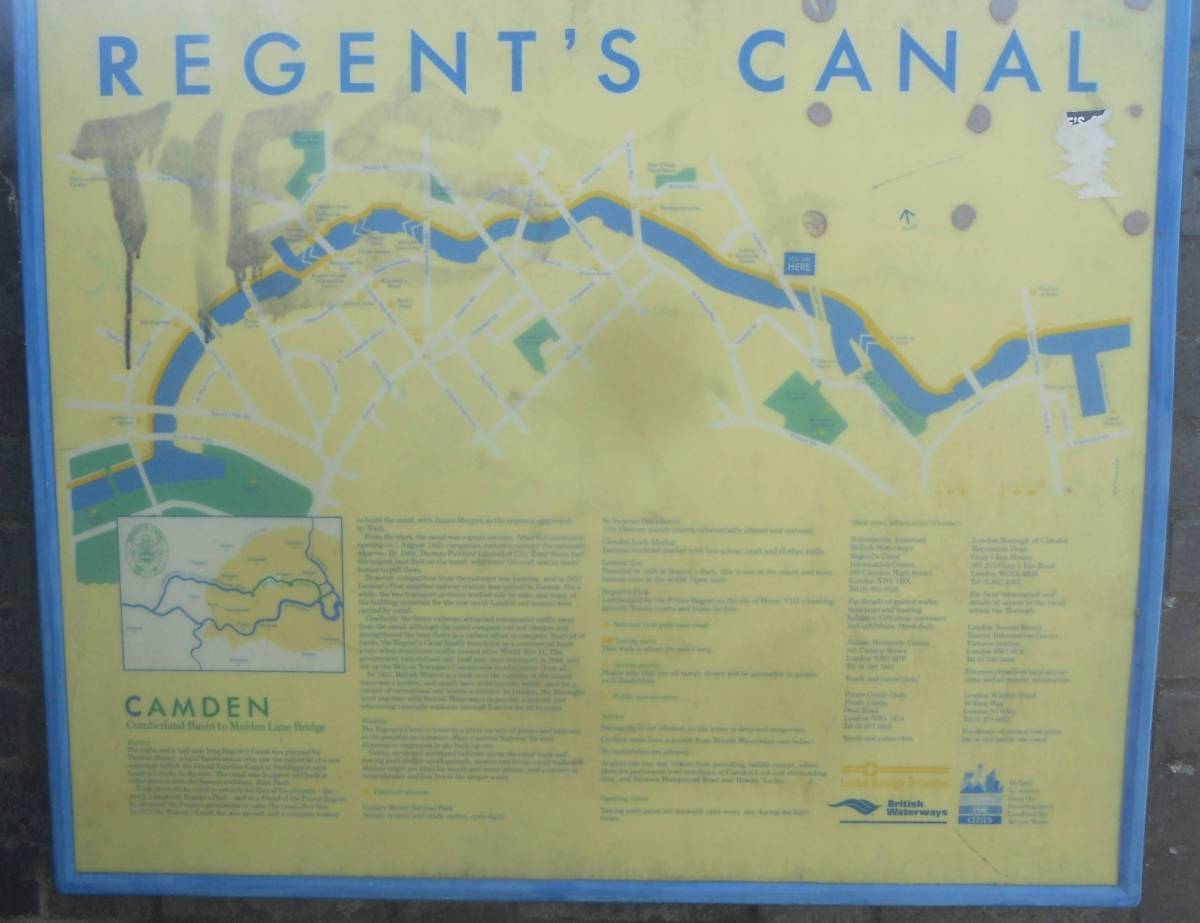

The eight and a half mile long Regent's Canal was planned by Thomas Homer, a businessman who saw the potential

for a new waterway to link the Grand Junction Canal at Paddington with London's docks to the east.

The canal was designed and built in collaboration with the famous architect, John Nash. Nash planned the canal to encircle another of his

projects - the newly completed Regent's Park - and as a friend of the Prince Regent he obtained the Prince's permission to name the canal after him.

In 1812 the Regent's Canal Act was passed and a company formed to build the canal.

James Morgan was appointed by Nash as the engineer.

From the start, the canal was a great success. After the ceremonial opening on 1st August 1820, companies rushed to occupy the canalside wharves. By 1840 Thomas Pickford Limited of City Road Basin had some 120 craft with as many horses to pull them - the largest boat fleet on the canal. However, competition from the railways was looming and in 1837 London's first mainland railway station was opened at Euston. For a while the two transport systems worked side by side and many of the building materials for the new north London rail termini were carried by canal. Gradually the faster railways attracted commercial traffic away from the canal, although the canal company cut tolls and strengthened the boat fleets in a valiant attempt to compete. Starved of funds the Regent's Canal finally foundered as a commercial trade route when munitions traffic ceased after World War II. The government nationalised rail, road and canal transport in 1948 and set up the British Transport Commission to administer them all. In 1963, British Waterways took over the running of 2000 miles of canal and river navigation which have become widely used for a variety of recreational and leisure activities. In London the Boroughs work together with British Waterways to provide a historic and interesting canalside walkway through London for all to enjoy. |

Greenspace Information Boards in Islington

|

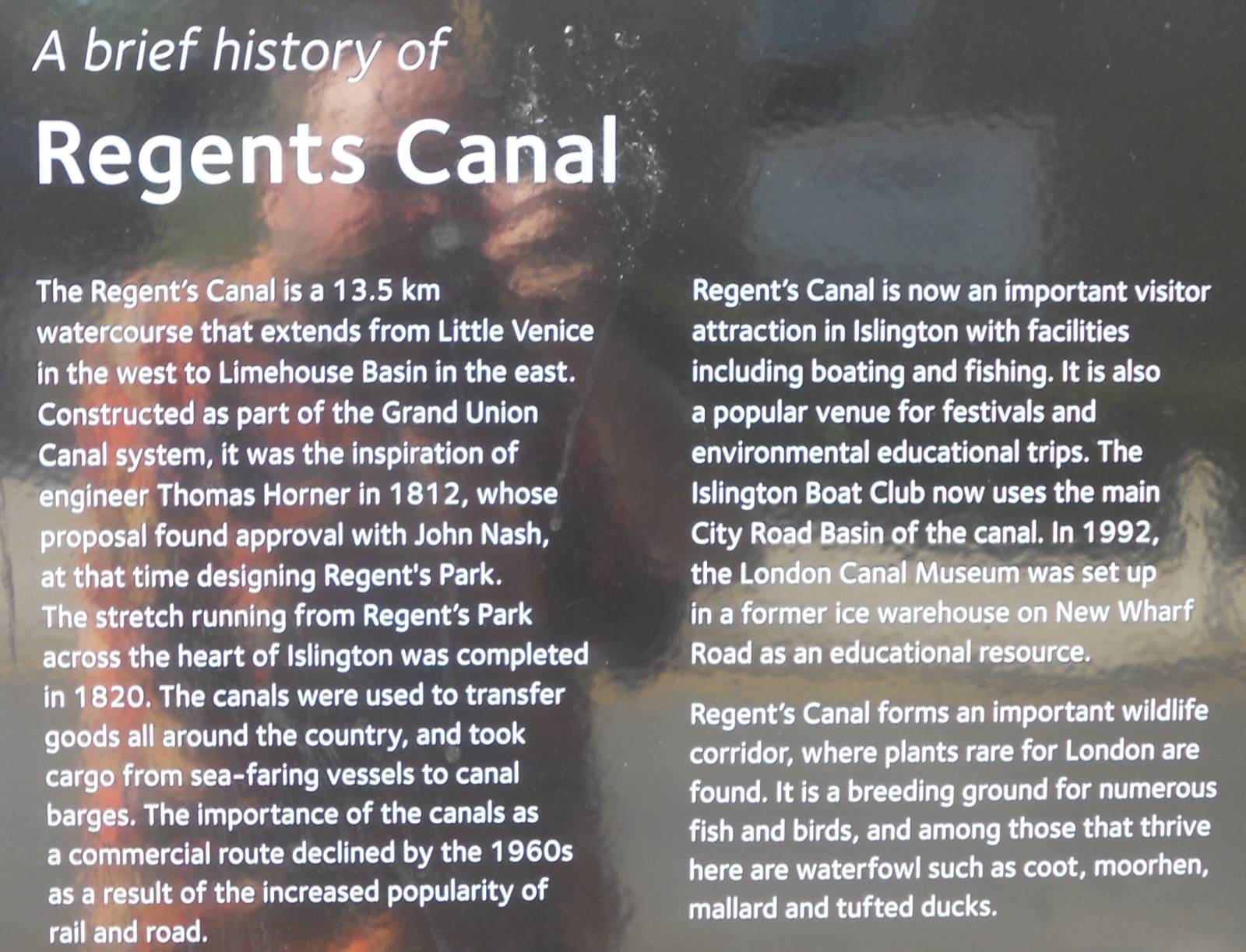

The Regent's Canal is a 13.5 km watercourse that extends from Little Venice in the west to Limehouse Basin in the east.

Constructed as part of the Grand Union Canal system, it was the inspiration of engineer Thomas Homer in 1812(?), whose

proposal found approval with John Nash, at that time designing Regent's Pak. The stretch running from Regent's Park across the

heart of Islington was completed in 1820. The canals were used to transfer goods all around the country, and took cargo from

sea-faring vessels to canal barges. The importance of the canals as a commercial route declined by the 1960s as a result

of the increased popularity of rail and road.

Regent's Canal is now an important visitor attraction in Islington with facilities including boating and fishing. It is also a popular venue for festivals and environmental educational trips. The Islington Boat Club now uses the main City Road Basin of the canal. In 1992 the London Canal Museum was set up in a former ice warehouse on New Wharf Road as an educational resource. Regent's Canal forms an important wildlife corridor, where plants rare for London are found. It is a breeding ground for numerous fish and birds, and among those that thrive here are waterfowl such as coot, moorhen, mallard and tufted ducks. |

Extracts from the London Canal Museum Website

To see the online version of this information please visit http://www.canalmuseum.org.uk/history/regents.htm

The Regent's Canal was built to link the Grand Junction Canal's Paddington Arm, which opened in 1801, with the Thames at Limehouse. One of the directors of the canal company was the famous architect John Nash. Nash was friendly with the Prince Regent, later King George IV, who allowed the use of his name for the project. The Regent's Canal Act was passed in 1812 and the company was formed to build and operate it. Nash's assistant, James Morgan, was appointed as the canal's Engineer. It was opened in two stages, from Paddington to Camden in 1816, and the rest of the canal in 1820.

Two serious setbacks, and shortage of money were to blame for the delay in completion. Firstly an innovative design of lock, the hydro pheumatic lock, invented by William Congreve, was built at Hampstead Road Lock. Congreve (later Sir William) was also famous for the invention of military rockets, and in the world of horology. The lock however was a failure, and in 1819 it had to be rebuilt to a conventional design.

Secondly Thomas Homer, once the canal's promoter, embezzled its funds in 1815 causing further financial problems. To build the canal cost £772,000, twice the original estimate of expenditure. The Canal was short of water supplies and it was necessary to dam the river Brent to create a reservoir to provide them, in 1835, extended in 1837 and 1854. A number of basins were built such as Battlebridge basin where the London Canal Museum now stands, which was opened in 1822. The main centre of trade was the Regent's Canal Dock, a point for seaborne cargo to be unloaded onto canal boats. Cargo from abroad, including ice destined for what is now the museum, was unloaded there and continued its journey on barges. City Road Basin was the second most important traffic centre, handling incoming inland freight, to a large extent.

By the 1840s the railways were taking traffic from the canals and there were attempts made, without success, to turn the canal into a railway at various times during the 19th Century. The explosion at Macclesfield Bridge (pictured in 2000) of 1874 was a famous incident in the canal's history, in which a gunpowder barge blew up, destroying the bridge and sending debris in all directions.

In the late 1920's talks took place between the Regent's Canal, the Grand Junction Canal, and the Warwick Canals, resulting, in 1929, in a merger between them. The Regent's Canal Company bought the canal assets of the other two parties and the new enlarged undertaking was renamed as the Grand Union Canal Company.

In the latter part of the second world war (1939-45) traffic increased on the canal system as an alternative to the hard pressed railways. Stop gates were installed near King's Cross to limit flooding of the railway tunnel below, in the event that the canal was breached by German bombs. Along with other transport systems the canal was nationalised in 1948, coming under the Docks and Inland Waterways Executive, a part of the British Transport Commission, which traded under the name "British Waterways". The British Transport Commission was split up in 1963 and the British Waterways Board , who still own and operate the canals, took over. They now also use the name British Waterways.

image : Regent's Canal Emblem

The last horse drawn commercial traffic was carried in 1956 following the introduction of motor tractors three years previously. By the late 1960's commercial traffic had all but vanished. The canal has since become a leisure facility with increased use of the towpath which has been opened up to the public. Boat trips are regularly available especially between Camden and the picturesque Little Venice in west London where the canal meets the Grand Junction near Paddington.

Key Dates in the Regent's Canal's History

| Year | Event |

|---|---|

| 1802 | Thomas Homer proposed a canal between the Paddington Canal, and the river Thames at Limehouse |

| 1810 | The Maonor of St. Pancras, including land needed for the canal route was bought at auction by William Agar, for £8,000 |

| 1811 | Homer approached the architect John Nash, who was building Regent's Park. Nash showed an interest in the canal running through the park. |

| 1812 | An Act of Parliament granted authority for the canal to be built and the Company of Proprietors of the Regent's Canal was formed and held its first meeting. Appointments were made: John Nash, Director, James Morgan, Engineer, architect, and land surveyor, Homer, Superintendant. Work began on 7th October, in Regent's Park |

| 1813 | A further Act of Parliament was passed to authorise the construction of the branch to Cumberland Market, near what is now Euston Station. A number of workmen died during the construction work. |

| 1814 | William Congreve, an inventor, approached the company with a patent for a hydro-pneumatic double balance lock. An attempt was made to build this at Hamstead Lock, but it was not successful and was abandoned in 1818. |

| 1815 | The year was marked by fighting between canal workers and the gardeners employed by landowner Mr Agar, and by the embeszzlement of funds by Homer, the Superintendant. Subscribers to the Comapny were asked to contribute more funds. Homer was caught, and sentenced to transportation. In the autumn construction work came to a standstill due to lack of funds. |

| 1816 | An Act of Parliament permitted the Company to act as a supplier of water to the Grand Junction Canal, and also sought to settle the dispute with Agar over land. The first part of the canal, from Paddington to Camden, was opened. |

| 1817 | The work on the construction of the Canal stopped again due to financial problems. However, the Comany was able to borrow money from the government under a scheme for relief of unemployment amongst the poor. |

| 1818 | The Company finally reached agreement with Agar over land, paying him a very high price for it. |

| 1819 | Islington Tunnel, three quarters of a mile long (878 metres) was completed. A fourth Act of Parliament authorised a branch to City Road, and the enlargement of what became the Regent's Canal Dock, at Limehouse, to cater for ships. Work began in the autumn to rebuild Hamstead Road Lock as a conventional lock. |

| 1820 | The canal was opened at 11 a.m on 1st August 1820. It had cost £772,000 to build - twice the original estimate. 120,000 tons of cargo were carried in the Canal's first year |

| 1822 | Opening of Horsfall Basin, now known as Battlebridge Basin. |

| 1826 | Wenlock basin was contructed. A steam chain tug was introduced in Islington Tunnel to reduce bottlenecks caused by boatman manually "legging" through it. The tug service continued until the 1930s. |

| 1835 | The Regent's Canal Company took over the concession from the Grand Junction Canal Company to build the Brent Reservoir by damming the river Brent at Hendon. |

| 1845 | The Company received an offer to convert the canal between Paddington and City Road basin into a railway. This was approved when the offer was increased to £1 million, but the finance could not be raised. |

| 1847 | Towing on the canal became the responsibility of the Company, which provided its own horses and added a charge for this service to its tolls. |

| 1854 | The size of Brent Reservoir was increased to meet the need for water |

| 1874 | A barge carrying gunpowder exploded on 2nd October at 4.55 in the morning, at Macclesfield Bridge. The bridge was destroyed and three crew members were killed. The canal was closed for four days. This bridge has become known as "Blow Up Bridge". |

| 1883 | Failure of a further attempt to buy the Canal for £1,275,000 and turn it into a railway. |

| 1914 | On 1st March, the Canal was taken into the control of the Board of Trade, because of the war. This control lasted until 31st August 1920 |

| 1929 | The Regent's Canal purchased the canal assets of the Grand Junction Canal, and of the Warwick canals, and the enlarged concern became called the Grand Union Canal. |

| 1942 | Cumberland Basin and arm were filled in with rubble from buildings damaged during the Second World War. |

| 1948 | Nationalisation of most UK railways, canals, and some road transport under the Transport Act 1947. The Regent's Canal became part of the British Transport Commission's system. The Commission's Docks and Inland Waterways Executive became responsible for the canal, trading under the name "British Waterways" |

| 1953 | Narrow tractors started to replace horses on the canal towpath |

| 1956 | The last horse drawn cargo travels along the Canal |

| 1963 | Reorganisation of the nationalised transport industry saw the break-up of the British Transport Commission and the canal was taken over by the new British Waterways Board. |

| 1968 | Old Limehouse Lock, on the Limehouse Cut, was filled in and a new connection was built between the Regent's Canal and the Limehouse Cut. The City of Westminster opened towpaths within its boundaries to the public for recreational use. |

| 1974 | Camden Council followed the Westminster lead by opening towpaths within its boundaries to the public. |

| 1979 | A further part of City Road Basin was filled in. Some of it, south of City Road itself, had been filled in in the 1930's. The towpaths were used as a route for electricity cables, underground. |

| 1992 | Opening of the London Canal Museum by HRH The Princess Royal on 9th March |

| 1996 | Formation of London's Waterway Partnership by British Waterways and a range of other interested organisations to bid for a programme to regenerate the canal under the government's Single Regeneration Budget. |

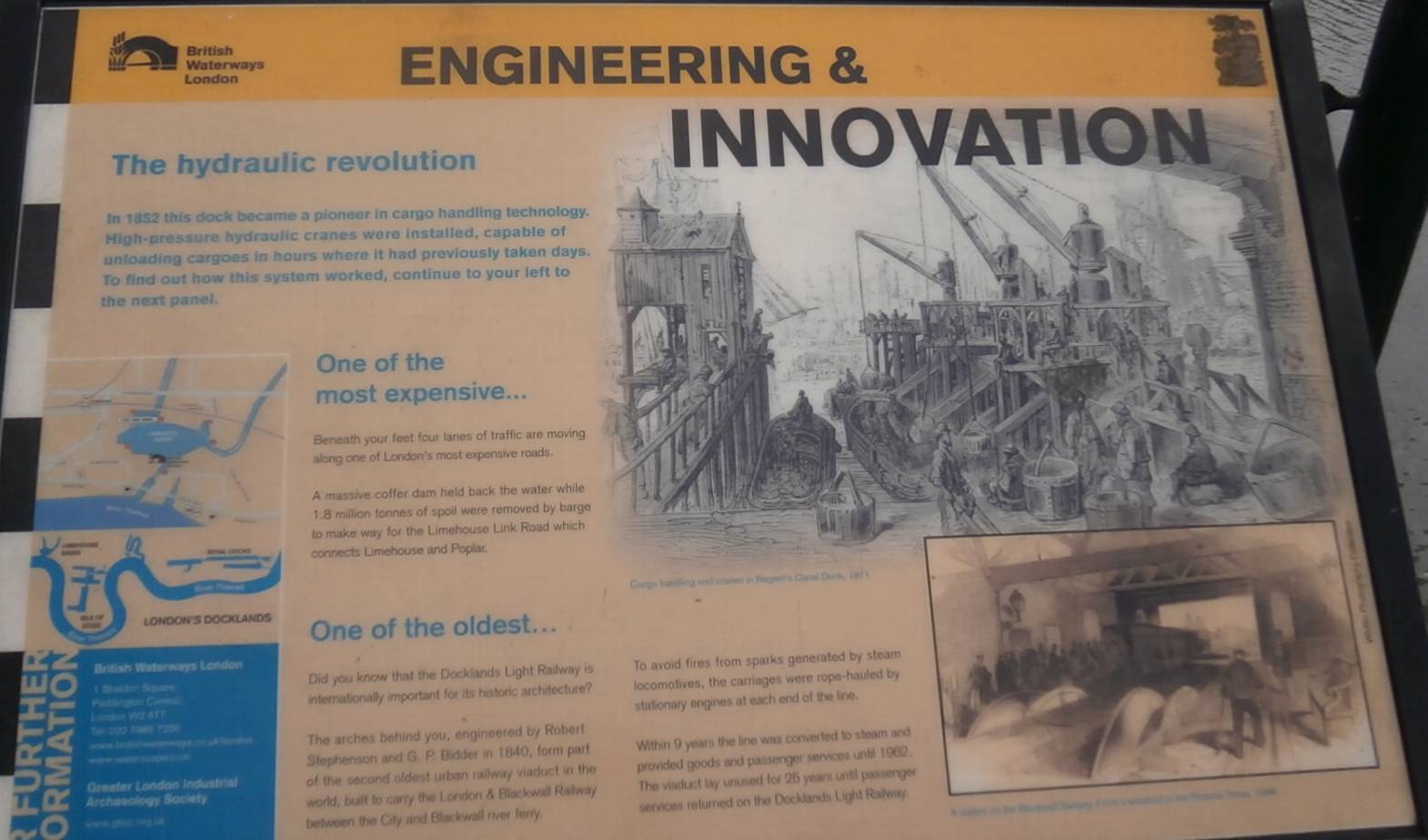

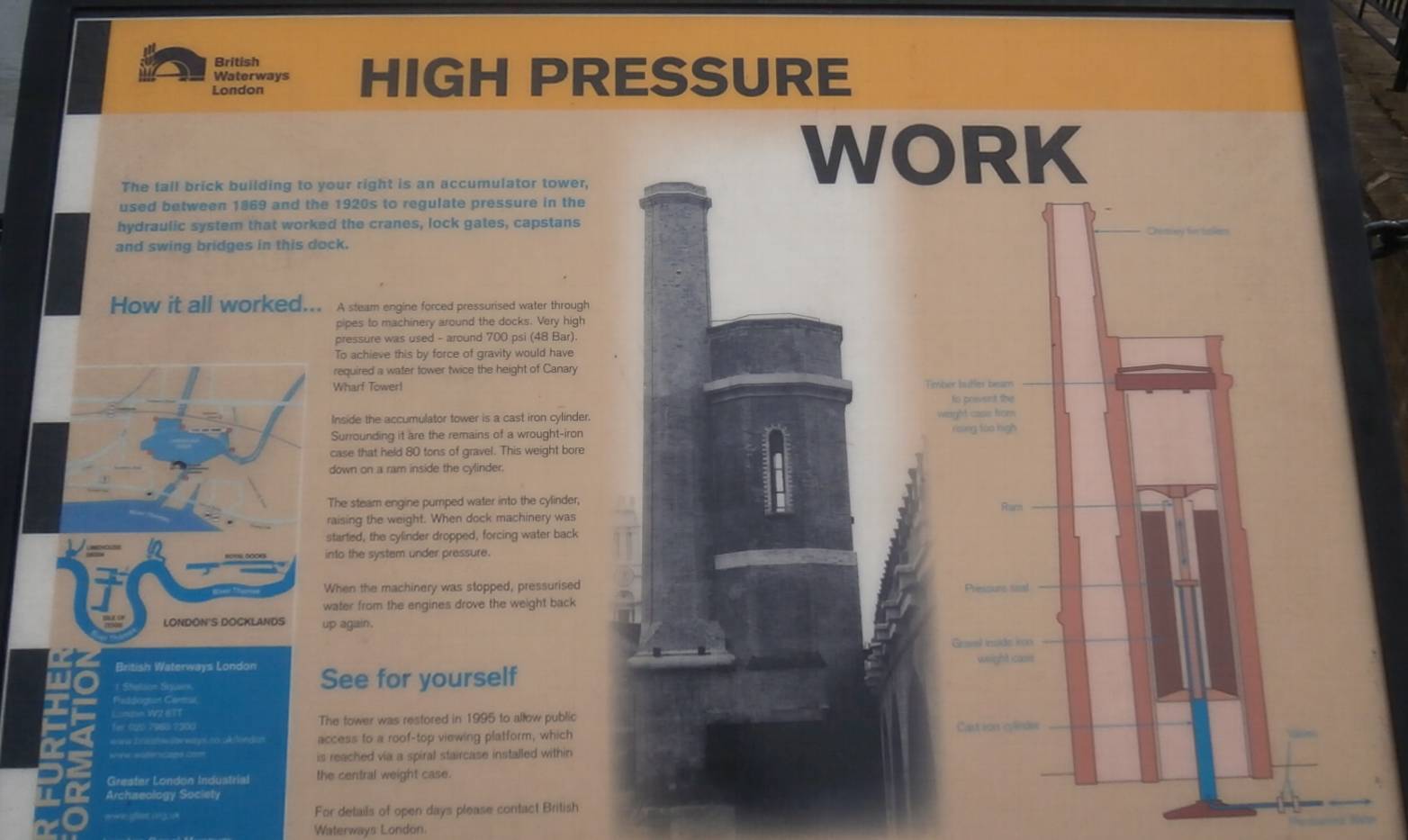

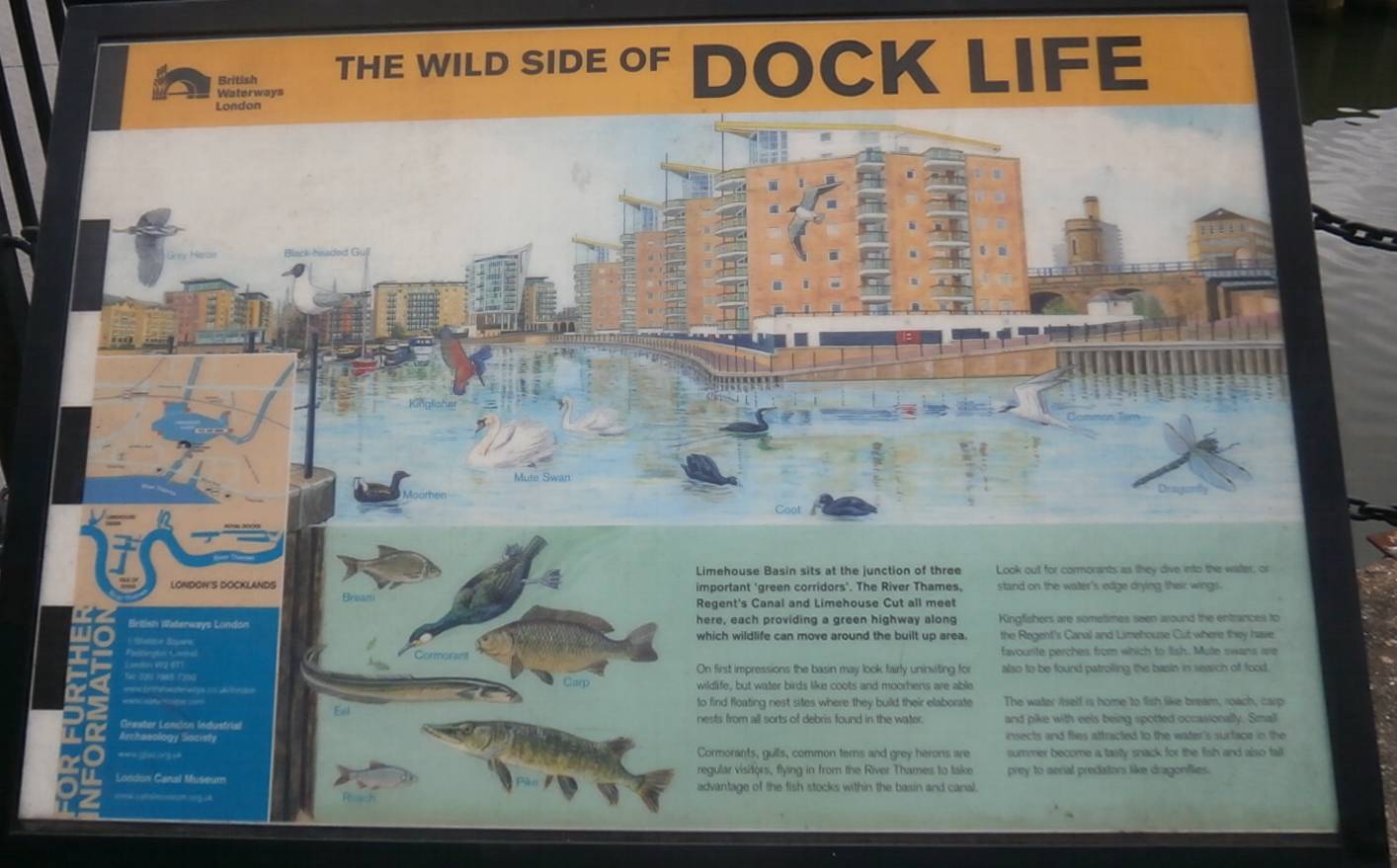

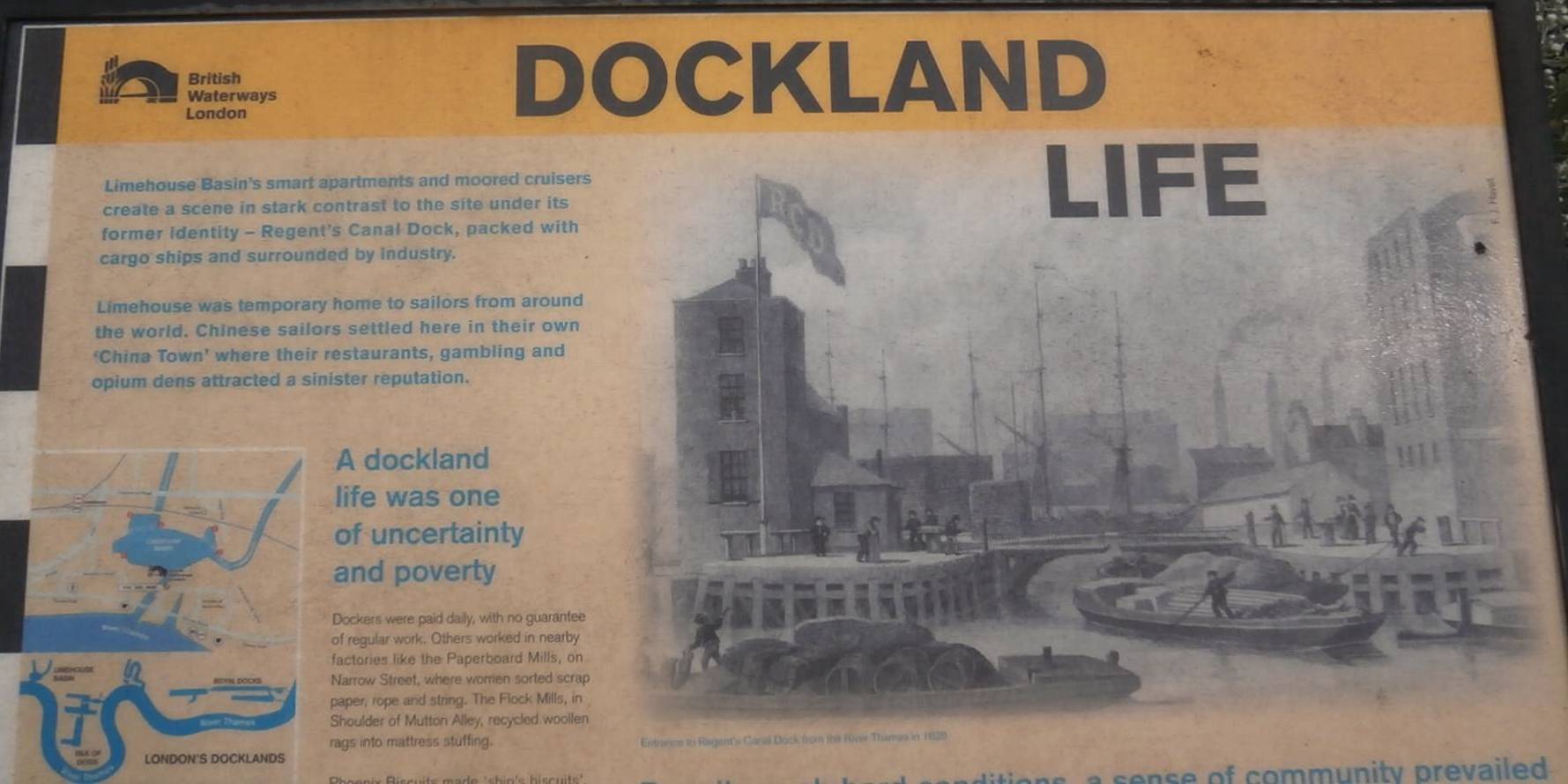

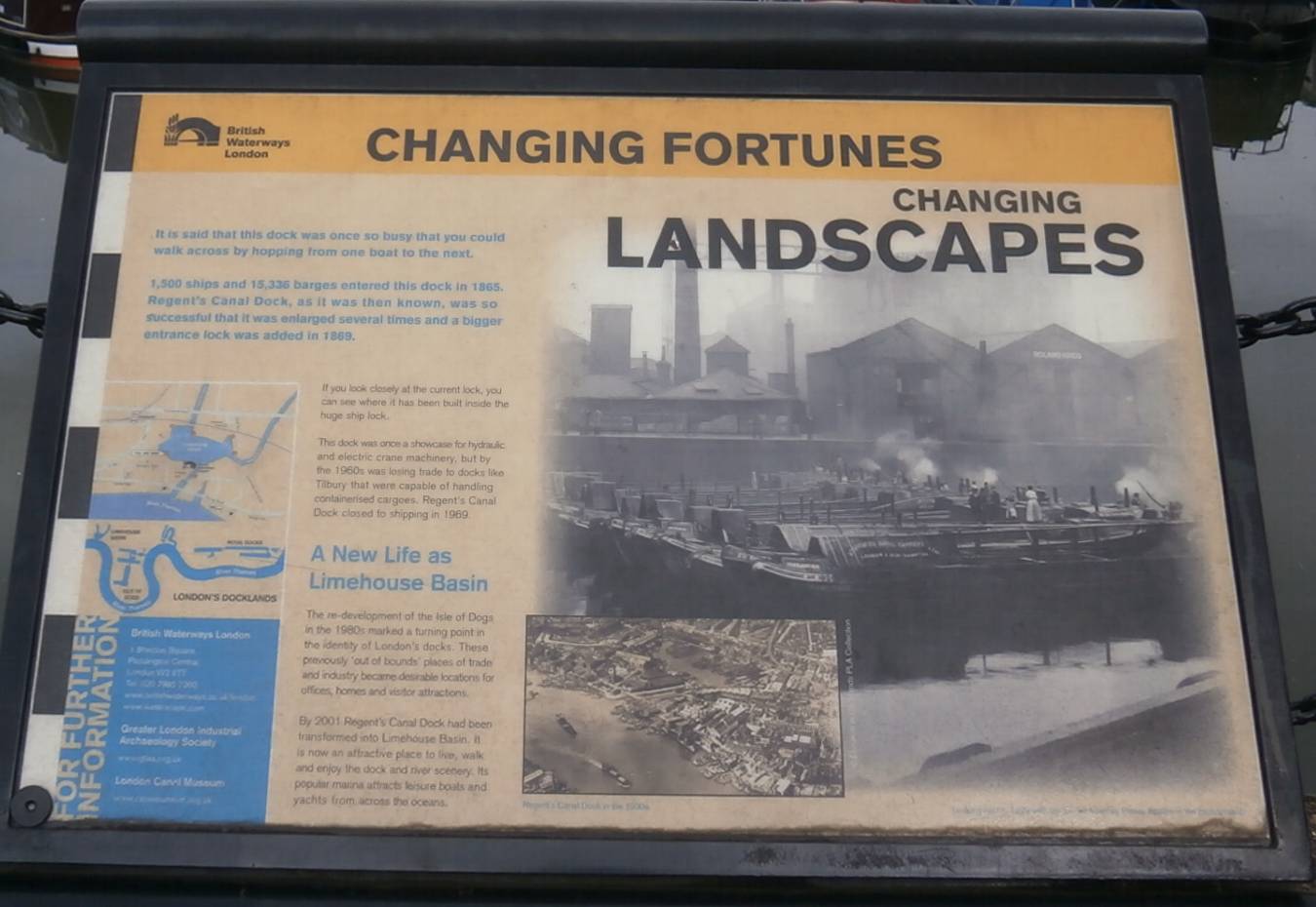

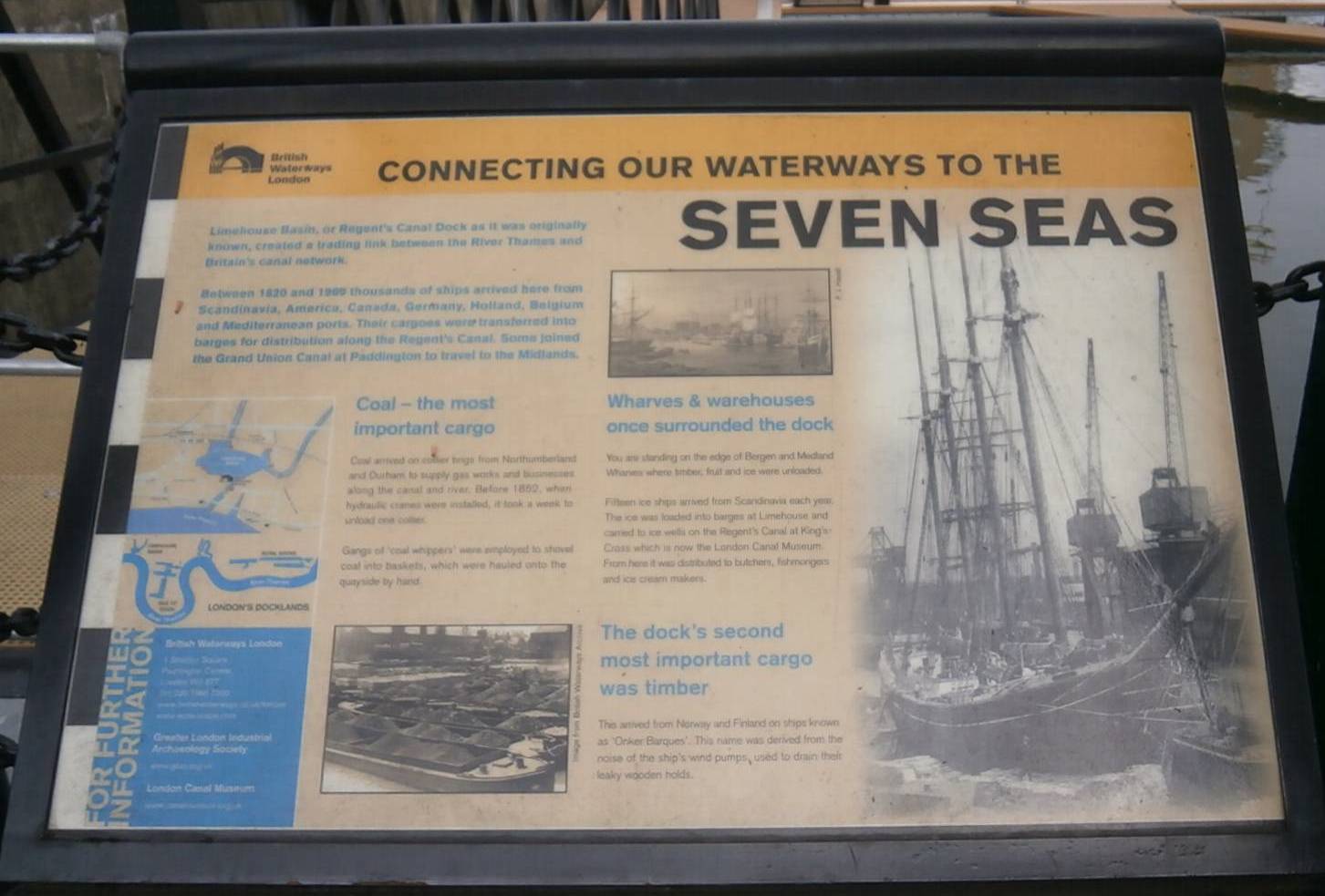

Information Boards at Limehouse

|

|

|

|

|

|